Mapping Categorical Predictors to Numeric With Target Encoding

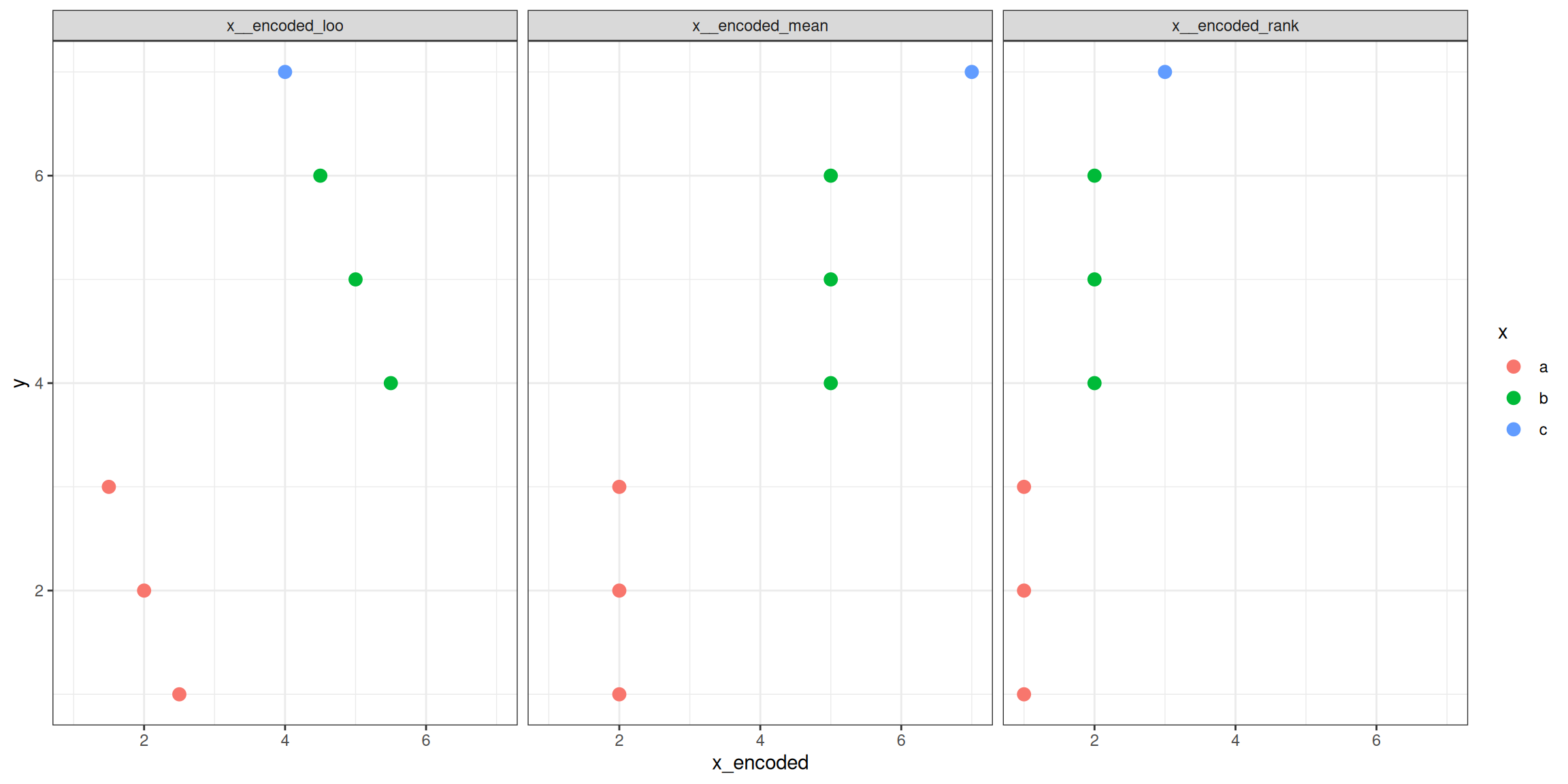

Target encoding of a toy data frame performed with collinear::target_encoding_lab()

Target encoding of a toy data frame performed with collinear::target_encoding_lab()

Summary

Categorical predictors are annoying stringy monsters that can turn any data analysis and modeling effort into a real annoyance. The explains how to deal with these types of predictors using methods such as one-hot encoding (please don’t) or target encoding, and provides insights into their mechanisms and quirks.

Key Highlights:

-

Categorical Predictors are Kinda Annoying: This section discusses the common issues encountered with categorical predictors during data analysis.

-

One-Hot Encoding Pitfalls: While discussing one-hot encoding, the post focuses on its limitations, including dimensionality explosion, increased multicollinearity, and sparsity in tree-based models.

-

Intro to Target Encoding: Introducing target encoding as an alternative, the post explains its concept, illustrating the basic form with mean encoding and subsequent enhancements with additive smoothing, leave-one-out encoding, and more.

-

Handling Sparsity and Repetition: It emphasizes the potential pitfalls of target encoding, such as repeated values within categories and their impact on model performance, prompting the exploration of strategies like white noise addition and random encoding to mitigate these issues.

-

Target Encoding Lab: The post concludes with a detailed demonstration using the

collinear::target_encoding_lab()function, offering a hands-on exploration of various target encoding methods, parameter combinations, and their visual representations.

The post intends to serve as a useful resource for data scientists exploring alternative encoding techniques for categorical predictors.

Resources

- Interactive notebook of this post.

- A preprocessing scheme for high-cardinality categorical attributes in classification and prediction problems

- Extending Target Encoding

- Target encoding done the right way.

R packages

This tutorial requires the development version (>= 1.0.3) of the newly released R package

collinear, and a few more.

#required

install.packages("collinear")

install.packages("fastDummies")

install.packages("rpart")

install.packages("rpart.plot")

install.packages("dplyr")

install.packages("ggplot2")

Categorical Predictors Can Be Annoying

I bet you have experienced it during an Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) or a feature selection for model training and the likes. You likely had a nice bunch of numerical predictors, and then some things like “sampling_location”, “region_name”, “favorite_color”, or any other type of character or factor columns. And you had to branch your code to deal with numeric and categorical variables separately. Or maybe chose to ignore them, as I have done plenty of times.

That’s why many efforts have been made to convert them to numeric and kill the problem at once. And now we all have two problems to solve instead.

Let me go ahead and illustrate the issue. There is a data frame in the collinear R package named vi_smol, with one response variable named vi_numeric, and several numeric and categorical predictors in the vector vi_predictors.

data(

vi_smol,

vi_predictors

)

dplyr::glimpse(vi_smol)

## Rows: 610

## Columns: 65

## $ longitude <dbl> 43.77903, 25.24569, 106.31236, -43.10431, -…

## $ latitude <dbl> 3.129027, 6.662361, -6.712639, -16.545973, …

## $ vi_numeric <dbl> 0.33, 0.60, 0.61, 0.48, 0.77, 0.61, 0.28, 0…

## $ vi_counts <int> 330, 600, 610, 480, 770, 610, 280, 200, 690…

## $ vi_binomial <int> 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1…

## $ vi_categorical <chr> "medium", "very_high", "very_high", "high",…

## $ vi_factor <fct> medium, very_high, very_high, high, very_hi…

## $ koppen_zone <chr> "BSh", "Aw", "Af", "Aw", "Am", "Aw", "BSh",…

## $ koppen_group <chr> "Arid", "Tropical", "Tropical", "Tropical",…

## $ koppen_description <chr> "steppe, hot", "savannah", "rainforest", "s…

## $ soil_type <fct> Leptosols, Acrisols, Cambisols, Leptosols, …

## $ topo_slope <int> 0, 0, 4, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 3, 5, 0, 1…

## $ topo_diversity <int> 17, 23, 30, 24, 22, 24, 20, 15, 23, 21, 24,…

## $ topo_elevation <int> 368, 654, 744, 831, 181, 159, 20, 1164, 96,…

## $ swi_mean <dbl> 12.4, 64.6, 55.7, 44.9, 61.1, 48.9, 27.0, 2…

## $ swi_max <dbl> 25.3, 89.8, 68.2, 69.5, 77.4, 80.0, 67.3, 5…

## $ swi_min <dbl> 5.5, 28.0, 24.6, 13.8, 22.9, 19.5, 5.7, 16.…

## $ swi_range <dbl> 19.8, 61.8, 43.6, 55.6, 54.5, 60.5, 61.6, 4…

## $ soil_temperature_mean <dbl> 28.4, 24.5, 22.4, 22.8, 24.6, 24.1, 28.7, 2…

## $ soil_temperature_max <dbl> 39.5, 36.2, 27.6, 34.6, 30.5, 34.1, 43.6, 4…

## $ soil_temperature_min <dbl> 20.4, 16.1, 17.2, 13.0, 19.6, 13.7, 15.2, 4…

## $ soil_temperature_range <dbl> 19.1, 20.2, 10.4, 21.6, 11.0, 20.4, 28.3, 4…

## $ soil_sand <int> 37, 49, 26, 39, 39, 28, 64, 76, 63, 68, 34,…

## $ soil_clay <int> 29, 28, 35, 34, 25, 30, 18, 11, 8, 20, 20, …

## $ soil_silt <int> 33, 21, 38, 25, 35, 40, 16, 11, 27, 10, 44,…

## $ soil_ph <dbl> 7.8, 5.7, 5.4, 5.7, 5.5, 5.4, 6.1, 7.6, 5.1…

## $ soil_soc <dbl> 11.9, 19.8, 69.8, 14.1, 23.4, 23.6, 5.5, 4.…

## $ soil_nitrogen <dbl> 1.0, 1.6, 4.0, 1.7, 1.9, 1.4, 0.5, 0.5, 1.3…

## $ solar_rad_mean <dbl> 22.821, 24.977, 12.900, 22.817, 22.090, 20.…

## $ solar_rad_max <dbl> 29.476, 27.272, 15.344, 28.289, 27.280, 26.…

## $ solar_rad_min <dbl> 12.567, 21.772, 9.589, 18.853, 19.268, 16.1…

## $ solar_rad_range <dbl> 16.909, 5.500, 5.755, 9.436, 8.012, 10.751,…

## $ growing_season_length <dbl> 96, 295, 365, 293, 365, 330, 176, 47, 365, …

## $ growing_season_temperature <dbl> 26.45, 25.15, 22.45, 22.15, 25.45, 25.05, 2…

## $ growing_season_rainfall <dbl> 502.6, 1476.2, 4867.0, 1048.3, 2067.5, 1811…

## $ growing_degree_days <dbl> 9729.0, 9360.7, 8181.9, 8044.5, 9291.1, 923…

## $ temperature_mean <dbl> 26.65, 25.65, 22.45, 22.05, 25.45, 25.35, 2…

## $ temperature_max <dbl> 35.65, 35.25, 25.85, 28.25, 30.65, 35.35, 3…

## $ temperature_min <dbl> 20.35, 20.35, 18.45, 14.25, 19.45, 13.65, 1…

## $ temperature_range <dbl> 15.3, 14.9, 7.4, 14.0, 11.2, 21.7, 19.8, 27…

## $ temperature_seasonality <dbl> 132.9, 140.6, 33.5, 159.4, 114.4, 329.3, 19…

## $ rainfall_mean <int> 505, 1476, 4867, 1048, 2067, 1811, 699, 299…

## $ rainfall_min <int> 0, 3, 216, 4, 51, 8, 0, 0, 81, 7, 78, 5, 0,…

## $ rainfall_max <int> 131, 239, 627, 241, 300, 328, 227, 60, 132,…

## $ rainfall_range <int> 130, 235, 410, 236, 249, 320, 227, 60, 51, …

## $ evapotranspiration_mean <dbl> 158.80, 141.64, 113.45, 136.53, 127.05, 118…

## $ evapotranspiration_max <dbl> 190.38, 161.02, 132.85, 166.99, 153.15, 164…

## $ evapotranspiration_min <dbl> 138.40, 126.76, 90.16, 95.43, 95.26, 74.33,…

## $ evapotranspiration_range <dbl> 51.98, 34.26, 42.70, 71.56, 57.90, 90.40, 6…

## $ cloud_cover_mean <int> 26, 45, 61, 36, 49, 38, 31, 13, 33, 19, 43,…

## $ cloud_cover_max <int> 43, 58, 82, 57, 69, 73, 51, 24, 43, 32, 54,…

## $ cloud_cover_min <int> 14, 28, 39, 21, 22, 13, 16, 4, 24, 9, 31, 3…

## $ cloud_cover_range <int> 28, 30, 43, 35, 47, 60, 35, 19, 18, 22, 22,…

## $ aridity_index <dbl> 0.28, 0.89, 4.07, 0.73, 1.48, 1.25, 0.36, 0…

## $ humidity_mean <dbl> 56.79, 55.46, 72.83, 58.50, 65.05, 63.21, 4…

## $ humidity_max <dbl> 62.58, 65.67, 77.94, 62.07, 69.35, 73.19, 6…

## $ humidity_min <dbl> 49.74, 38.20, 68.70, 54.10, 57.98, 49.59, 3…

## $ humidity_range <dbl> 12.84, 27.47, 9.24, 7.97, 11.37, 23.60, 27.…

## $ biogeo_ecoregion <chr> "Northern Swahili coastal forests", "Northe…

## $ biogeo_biome <chr> "Tropical & Subtropical Moist Broadleaf For…

## $ biogeo_realm <chr> "Afrotropic", "Afrotropic", "Indomalayan", …

## $ country_name <chr> "Somalia", "Central African Republic", "Ind…

## $ continent <chr> "Africa", "Africa", "Asia", "South America"…

## $ region <chr> "Africa", "Africa", "Asia", "Americas", "Am…

## $ subregion <chr> "Eastern Africa", "Middle Africa", "South-E…

The categorical variables in this data frame are identified below:

vi_categorical <- collinear::identify_categorical_variables(

df = vi_smol,

predictors = vi_predictors

)

vi_categorical

## $valid

## [1] "koppen_zone" "koppen_group" "koppen_description"

## [4] "soil_type" "biogeo_ecoregion" "biogeo_biome"

## [7] "biogeo_realm" "country_name" "continent"

## [10] "region" "subregion"

##

## $invalid

## NULL

And finally, their number of categories:

data.frame(

name = vi_categorical$valid,

categories = lapply(

X = vi_categorical$valid,

FUN = function(x) length(unique(vi_smol[[x]]))

) |>

unlist()

) |>

dplyr::arrange(

dplyr::desc(categories)

)

## name categories

## 1 biogeo_ecoregion 227

## 2 country_name 103

## 3 soil_type 25

## 4 koppen_zone 23

## 5 subregion 21

## 6 koppen_description 17

## 7 biogeo_biome 13

## 8 biogeo_realm 7

## 9 continent 7

## 10 region 6

## 11 koppen_group 5

Some of them, like country_name and biogeo_ecoregion, have a cardinality high enough to ruin our day, don’t they? But ok, let’s start with one with a moderate number of categories, like koppen_zone. This variable has 23 categories representing climate zones.

sort(unique(vi_smol$koppen_zone))

## [1] "Af" "Am" "Aw" "BSh" "BSk" "BWh" "BWk" "Cfa" "Cfb" "Cfc" "Csa" "Csb"

## [13] "Cwa" "Cwb" "Dfa" "Dfb" "Dfc" "Dsb" "Dsc" "Dwa" "Dwb" "Dwc" "ET"

One-hot Encoding is here…

Let’s use it as predictor of vi_numeric in a linear model and take a look at the summary.

stats::lm(

formula = vi_numeric ~ koppen_zone,

data = vi_smol

) |>

summary()

##

## Call:

## stats::lm(formula = vi_numeric ~ koppen_zone, data = vi_smol)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -0.42558 -0.05528 -0.00528 0.05250 0.31667

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 0.65558 0.01391 47.134 < 2e-16 ***

## koppen_zoneAm 0.01202 0.02294 0.524 0.600520

## koppen_zoneAw -0.13228 0.01642 -8.054 4.50e-15 ***

## koppen_zoneBSh -0.33225 0.02111 -15.741 < 2e-16 ***

## koppen_zoneBSk -0.41415 0.01906 -21.731 < 2e-16 ***

## koppen_zoneBWh -0.52030 0.01616 -32.200 < 2e-16 ***

## koppen_zoneBWk -0.52851 0.01991 -26.547 < 2e-16 ***

## koppen_zoneCfa -0.06158 0.02294 -2.685 0.007467 **

## koppen_zoneCfb -0.07415 0.02428 -3.054 0.002361 **

## koppen_zoneCfc 0.08442 0.09226 0.915 0.360567

## koppen_zoneCsa -0.22058 0.04768 -4.627 4.58e-06 ***

## koppen_zoneCsb -0.03558 0.05446 -0.653 0.513817

## koppen_zoneCwa -0.12110 0.02192 -5.526 4.94e-08 ***

## koppen_zoneCwb -0.24858 0.03202 -7.763 3.70e-14 ***

## koppen_zoneDfa -0.20808 0.03512 -5.925 5.32e-09 ***

## koppen_zoneDfb -0.16834 0.02192 -7.681 6.64e-14 ***

## koppen_zoneDfc -0.21641 0.02324 -9.312 < 2e-16 ***

## koppen_zoneDsb -0.36558 0.04309 -8.483 < 2e-16 ***

## koppen_zoneDsc -0.32558 0.06598 -4.935 1.05e-06 ***

## koppen_zoneDwa -0.34308 0.02978 -11.522 < 2e-16 ***

## koppen_zoneDwb -0.21958 0.04309 -5.095 4.70e-07 ***

## koppen_zoneDwc -0.31433 0.03512 -8.951 < 2e-16 ***

## koppen_zoneET -0.35558 0.09226 -3.854 0.000129 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.09121 on 587 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.8195, Adjusted R-squared: 0.8127

## F-statistic: 121.1 on 22 and 587 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

Look at that. What the hell happened there? Well, linear models need to create numeric dummy variables to deal with categorical predictors. The function stats::model.matrix() does exactly that:

dummy_variables <- stats::model.matrix(

~ koppen_zone,

data = vi_smol

)

ncol(dummy_variables)

## [1] 23

dummy_variables[1:10, 1:10]

## (Intercept) koppen_zoneAm koppen_zoneAw koppen_zoneBSh koppen_zoneBSk

## 17401 1 0 0 1 0

## 24388 1 0 1 0 0

## 4775 1 0 0 0 0

## 26753 1 0 1 0 0

## 13218 1 1 0 0 0

## 26109 1 0 1 0 0

## 29143 1 0 0 1 0

## 10539 1 0 0 0 0

## 8462 1 0 0 0 0

## 4050 1 0 0 1 0

## koppen_zoneBWh koppen_zoneBWk koppen_zoneCfa koppen_zoneCfb

## 17401 0 0 0 0

## 24388 0 0 0 0

## 4775 0 0 0 0

## 26753 0 0 0 0

## 13218 0 0 0 0

## 26109 0 0 0 0

## 29143 0 0 0 0

## 10539 1 0 0 0

## 8462 0 0 1 0

## 4050 0 0 0 0

## koppen_zoneCfc

## 17401 0

## 24388 0

## 4775 0

## 26753 0

## 13218 0

## 26109 0

## 29143 0

## 10539 0

## 8462 0

## 4050 0

This function first creates an Intercept column with all ones. Then, for each original category except the first one (“Af”), a new column with value 1 in the cases where the given category was present and 0 otherwise is created. The category with no column (“Af”) is represented in these cases in the intercept where all other dummy columns are zero. This is, essentially, one-hot encoding with a little twist. You will find most people use the terms dummy variables and one-hot encoding interchangeably, and that’s ok. But in the end, the little twist of omitting the first category is what differentiates them. Most functions performing one-hot encoding, no matter their name, are creating as many columns as categories. That is for example the case of fastDummies::dummy_cols(), from the R package

fastDummies:

df <- fastDummies::dummy_cols(

.data = vi_smol[, "koppen_zone", drop = FALSE],

select_columns = "koppen_zone",

remove_selected_columns = TRUE

)

dplyr::glimpse(df)

## Rows: 610

## Columns: 23

## $ koppen_zone_Af <int> 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, …

## $ koppen_zone_Am <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, …

## $ koppen_zone_Aw <int> 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, …

## $ koppen_zone_BSh <int> 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, …

## $ koppen_zone_BSk <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, …

## $ koppen_zone_BWh <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, …

## $ koppen_zone_BWk <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, …

## $ koppen_zone_Cfa <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, …

## $ koppen_zone_Cfb <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, …

## $ koppen_zone_Cfc <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, …

## $ koppen_zone_Csa <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, …

## $ koppen_zone_Csb <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, …

## $ koppen_zone_Cwa <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, …

## $ koppen_zone_Cwb <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, …

## $ koppen_zone_Dfa <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, …

## $ koppen_zone_Dfb <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, …

## $ koppen_zone_Dfc <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, …

## $ koppen_zone_Dsb <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, …

## $ koppen_zone_Dsc <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, …

## $ koppen_zone_Dwa <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, …

## $ koppen_zone_Dwb <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, …

## $ koppen_zone_Dwc <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, …

## $ koppen_zone_ET <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, …

…to mess-up your models

As good as one-hot encoding is to fit linear models when predictors are categorical, it creates a couple of glaring issues that are hard to address when the number of encoded categories is high.

The first issue can easily be named the dimensionality explosion. If we created dummy variables for all categorical predictors in vi_smol, then we’d go from the original 58 predictors to a total of 967 new columns to handle. This alone can degrade the computational performance of a model due to increased data size.

The second issue is increased multicollinearity. One-hot encoded features are highly collinear, which makes obtaining accurate estimates for the coefficients of the encoded categories very hard. Look at the Variance Inflation Factors of the encoded Koppen zones, they have incredibly high values!

collinear::vif_df(

df = df,

quiet = TRUE

)

## vif predictor

## 1 180.1959 koppen_zone_Af

## 2 164.3623 koppen_zone_Am

## 3 83.2260 koppen_zone_Aw

## 4 73.9284 koppen_zone_BSh

## 5 70.7814 koppen_zone_BSk

## 6 57.9543 koppen_zone_BWh

## 7 51.3973 koppen_zone_BWk

## 8 51.3973 koppen_zone_Cfa

## 9 44.7446 koppen_zone_Cfb

## 10 44.7446 koppen_zone_Cfc

## 11 43.0665 koppen_zone_Csa

## 12 37.9963 koppen_zone_Csb

## 13 22.4630 koppen_zone_Cwa

## 14 18.9455 koppen_zone_Cwb

## 15 15.4040 koppen_zone_Dfa

## 16 15.4040 koppen_zone_Dfb

## 17 10.0469 koppen_zone_Dfc

## 18 10.0469 koppen_zone_Dsb

## 19 8.2493 koppen_zone_Dsc

## 20 6.4457 koppen_zone_Dwa

## 21 4.6361 koppen_zone_Dwb

## 22 2.8205 koppen_zone_Dwc

## 23 2.8205 koppen_zone_ET

On top of those issues, one-hot encoding also causes sparsity in tree-based models. Let me show you an example. Below I train a recursive partition tree using vi_numeric as response, and the one-hot encoded version of koppen_zone we have in df.

#add response variable to df

df$vi_numeric <- vi_smol$vi_numeric

#fit model using all one-hot encoded variables

koppen_zone_one_hot <- rpart::rpart(

formula = vi_numeric ~ .,

data = df

)

Now I do the same using the categorical version of koppen_zone in vi_smol.

koppen_zone_categorical <- rpart::rpart(

formula = vi_numeric ~ koppen_zone,

data = vi_smol

)

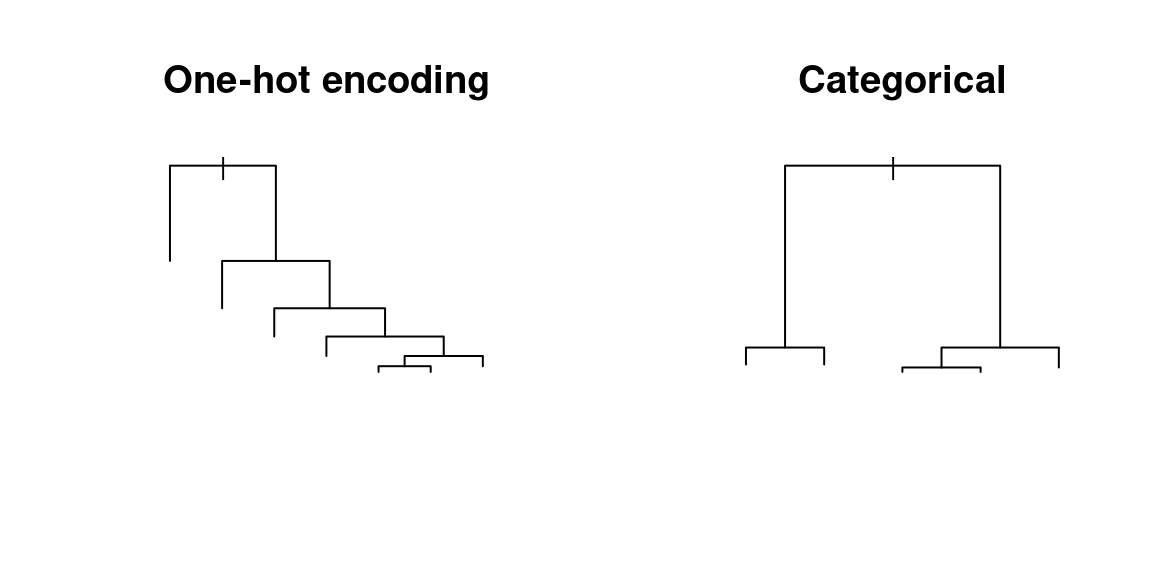

Finally, I am plotting the skeletons of these trees side by side (we don’t care about numbers here).

#plot tree skeleton

par(mfrow = c(1, 2))

plot(koppen_zone_one_hot, main = "One-hot encoding")

plot(koppen_zone_categorical, main = "Categorical")

Notice the stark differences in tree structure between both options. On the left, the tree trained on the one-hot encoded data only shows growth on one side! This is the sparsity I was talking about before. On the right side, however, the tree based on the categorical variable shows a balanced and healthy structure. One-hot encoded data can easily mess up a single univariate regression tree, so imagine what it can do to your fancy random forest model with hundreds of these trees.

In the end, the magic of one-hot encoding is in its inherent ability to create two or three problems for each one it promised to solve. We all know someone like that. Not so hot, if you ask me.

Target Encoding, Mean Encoding, and Dummy Variables (All The Same)

On a bright summer day of 2001, Daniele Micci-Barreca finally got sick of the one-hot encoding wonders and decided to publish his ideas on a suitable alternative others later named mean encoding or target encoding. He told the story himself 20 years later, in a nice blog post titled Extending Target Encoding.

But what is target encoding? Let’s start with a continuous response variable y (a.k.a the target) and a categorical predictor x.

Mean Encoding

In it’s simplest form, target encoding replaces each category in x with the mean of y across the category cases. This results in a new numeric version of x named x_encoded in the example below.

yx |>

dplyr::group_by(x) |>

dplyr::mutate(

x_encoded = mean(y)

)

## # A tibble: 7 × 3

## # Groups: x [3]

## y x x_encoded

## <int> <chr> <dbl>

## 1 1 a 2

## 2 2 a 2

## 3 3 a 2

## 4 4 b 5

## 5 5 b 5

## 6 6 b 5

## 7 7 c 7

Simple is good, right? But sometimes it’s not. In our toy case, the category “c” has only one case that maps directly to an actual value of y.Imagine the worst case scenario of x having one different category per row, then x_encoded would be identical to y!

Mean Encoding With Additive Smoothing

The issue can be solved by pushing the mean of y for each category in x towards the global mean of y by the weighted sample size of the category, as suggested by the expression

where:

y_mean <- mean(yx$y)

m <- 3

yx |>

dplyr::group_by(x) |>

dplyr::mutate(

x_encoded =

(dplyr::n() * mean(y) + m * y_mean) / (dplyr::n() + m)

)

## # A tibble: 7 × 3

## # Groups: x [3]

## y x x_encoded

## <int> <chr> <dbl>

## 1 1 a 3

## 2 2 a 3

## 3 3 a 3

## 4 4 b 4.5

## 5 5 b 4.5

## 6 6 b 4.5

## 7 7 c 4.75

So far so good! But still, the simplest implementations of target encoding generate repeated values for all cases within a category. This can still mess-up tree-based models a bit, because splits may happen again and again in the same values of the predictor. However, there are several strategies to limit this issue as well.

Leave-one-out Target Encoding

In this version of target encoding, the encoded value of one case within a category is the mean of all other cases within the same category. This results in a robust encoding that avoids direct reference to the target value of the sample being encoded, and does not generate repeated values.

The code below implements the idea in a way so simple that it cannot even deal with one-case categories.

yx |>

dplyr::group_by(x) |>

dplyr::mutate(

x_encoded = (sum(y) - y) / (dplyr::n() - 1)

)

## # A tibble: 7 × 3

## # Groups: x [3]

## y x x_encoded

## <int> <chr> <dbl>

## 1 1 a 2.5

## 2 2 a 2

## 3 3 a 1.5

## 4 4 b 5.5

## 5 5 b 5

## 6 6 b 4.5

## 7 7 c NaN

Rank Encoding

This is a little different from all the other methods, because it does not map the categories to values from the target, but to the rank/order of the target means per category. It basically converts the categorical variable into an ordinal one arranged along with the target.

yx |>

dplyr::arrange(y) |>

dplyr::group_by(x) |>

dplyr::mutate(

x_encoded = dplyr::cur_group_id()

)

## # A tibble: 7 × 3

## # Groups: x [3]

## y x x_encoded

## <int> <chr> <int>

## 1 1 a 1

## 2 2 a 1

## 3 3 a 1

## 4 4 b 2

## 5 5 b 2

## 6 6 b 2

## 7 7 c 3

The Target Encoding Lab

The function collinear::target_encoding_lab() implements all these encoding methods, and allows defining different combinations of parameters. It was designed to help understand how they work, and maybe help make choices about what’s the right encoding for a given categorical predictor.

In the example below, the methods rank, mean, and leave-one-out are computed.

yx_encoded <- collinear::target_encoding_lab(

df = yx,

response = "y",

predictors = "x",

encoding_method = c("mean", "loo", "rank"),

overwrite = FALSE, #to keep original predictors intact

quiet = TRUE

)

dplyr::glimpse(yx_encoded)

## Rows: 7

## Columns: 5

## $ y <int> 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

## $ x <fct> a, a, a, b, b, b, c

## $ x__encoded_mean <dbl> 2, 2, 2, 5, 5, 5, 7

## $ x__encoded_loo <dbl> 2.5, 2.0, 1.5, 5.5, 5.0, 4.5, 4.0

## $ x__encoded_rank <int> 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 3

The function also allows to replace a given predictor with their selected encoding.

yx_encoded <- collinear::target_encoding_lab(

df = yx,

response = "y",

predictors = "x",

methods = "mean",

overwrite = TRUE,

quiet = TRUE

)

dplyr::glimpse(yx_encoded)

## Rows: 7

## Columns: 2

## $ y <int> 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

## $ x <dbl> 2.5, 2.0, 1.5, 5.5, 5.0, 4.5, 4.0

And that’s all about target encoding so far!

I have a post in my TODO list with a little real experiment comparing target encoding with one-hot encoding in tree-based models. If you are interested, stay tuned!

Cheers,

Blas